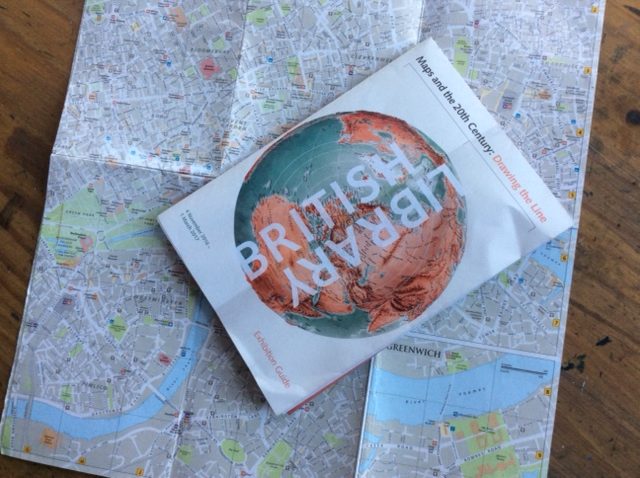

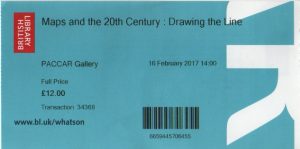

A trip to the British Library to see the exhibition of maps ‘Maps and the 20th Century – Drawing the Line’ before it closed (March 3rd 2017) seemed like a suitable finish to my ‘Hand Drawn Maps’ book for Thames and Hudson (although the cover is interminably still in progress – often the last part to be completed in a book project.)

The exhibition started with the statement that the 20th century was one of the most turbulent in history. Reflecting this, the space was divided into sections displaying maps made for different political and economic purposes. As always maps are made for a reason and geographical features are edited and curated with that in mind.

The exhibition opened with the idea of ‘Mapping a New World’ and I was struck by the creativity of modern cartographers and the need and opportunity to map in new ways as the world changed at an increasingly fast pace in the 20th century. Traditional hand drawn maps on paper began to disappear in favour of a variety of digital mapping systems and satellite images. These are all imaginative solutions to age old problems in showing a 3d landscape in a 2d format. For me, though, the heart of the place mapped and the inherent heart of the mapmaker became much harder to see.

The maps made for war were striking in their cold practicality yet, sometimes, had a weird kind of beauty about them. The 3d maps used on the battlefields of the Somme showed German and British trenches bleeding out across the fields in blue and red rivulets. A very necessary tool but their construction out of card cut and built up to show the contours of the landscape gave the maps an elegant sculptural quality. Despite this, it was hard to look at them from a purely aesthetic point of view. The general use of maps made for war as surveillance and propaganda tools promoted conflicts on a larger scale and with more sophistication. Here maps were displayed as weapons.

The maps made for resistance were interesting. The features the map maker chose to show clearly reflect their purpose. I loved the CND pacifist map which pointed out the public phone boxes available to activists protesting against cruise missiles in pre-mobile phone days. It was functional but had heart and humour about it.

The maps made for peace reminded me further how much they can be used to manipulate. Created in attempts to forge agreements between nations or explain new boundaries, maps could become ‘the catalyst for future conflict’, as the exhibition leaflet puts it. Maps in this section showed how frustrated soldiers were moved from one occupation to another, or how maps acted as tools to control the movements of refugees and the rebuilding of bombed cities. Perhaps those that struck me most were illustrated – those with jaunty optimistic pictures; maps looking forward to wished-for utopian worlds or looking back, reminding tired and hungry populations of mythical golden times. Maps can act as propoganda.

‘Mapping the Market’ charted the rise of maps used to document money, goods, economics. My heart sank at the chilliness of it all and I rushed through. ‘Mapping Movement’ displayed technological advances in charting geography with the advent of GPS. Ironically, the map I really wanted to look at was the poster showing wildlife migration flights across the USA, illustrated with a flock of native birds flying northwards.

I think my reaction to the exhibition told me more about myself than about maps in the 20th century really. I was attracted to those with an element of hand drawing in them, be that in the writing of place names or illustrations rather than the cold scientific ‘maps-as-infograms’. There were many maps displayed that functioned well with a political, scientific or economic purpose in mind but the maps I liked were the ones that had been made with love and exuberance and the sheer joy of describing a place.

The last map I saw was not in the ‘Maps of the 20th Century’ exhibition but in the ‘Treasures of the British Libary’ rooms. A large globe showing the constellations, perhaps over a metre in diameter, made in the 17th century by Coronelli. Once upon a time, it must have been painted in blues, indigos and golds and depicted the dancing stars – the twins and the goat, the water carrier, centaur and virgin. I doubt it was very scientifically accurate or particularly practical. But I liked its brass and wooden fittings and I liked its golden patina of age. What I liked most about it though, was that it had also been tanned by centuries of hands swinging the heavens around and people clearly marvelling with wonder and curiosity at such a beautiful object and what a mysterious world they still had to discover.